The Oceanic Whitetip are list of “threatened” species under the Endangered Species Act.

The also were apart of the largest shark attack know in history.

The Oceanic Whitetip Behaviour

The oceanic whitetip is usually solitary and slow-moving, and tends to cruise near the top of the water column, covering vast stretches of empty water scanning for possible food sources. Until the 16th century, sharks were known to mariners as “sea dogs” and the oceanic whitetip, the most common ship-following shark, exhibits dog-like behaviour when its interest is piqued: when attracted to something that appears to be food, its movements become more avid and it will approach cautiously but stubbornly, retreating and maintaining a safe distance if driven off, but ready to rush in if the opportunity presents itself. Oceanic whitetips are not fast swimmers, but they are capable of surprising bursts of speed. Whitetips commonly compete for food with silky sharks, making up for its comparatively leisurely swimming style with aggressive displays.

Groups often form when individuals converge on a food source, whereupon a feeding frenzy may occur. This seems to be triggered not by blood in the water or by bloodlust, but by the species’ highly strung and goal-directed nature (conserving energy between infrequent feeding opportunities when it is not slowly plying the open ocean). The oceanic whitetip is a competitive, opportunistic predator that exploits the resource at hand, rather than avoiding trouble in favour of a possibly easier future meal.

There does not seem to be segregation by sex and size. Whitetips follow schools of tuna or squid, and trail groups of cetaceans such as dolphins and pilot whales, scavenging their prey. Their instinct to follow is so strongly imprinted, from countless millennia following baitfish migrations, that they accompany ocean-going ships. When whaling took place in warm waters, oceanic whitetips were often responsible for much of the damage to floating carcasses.

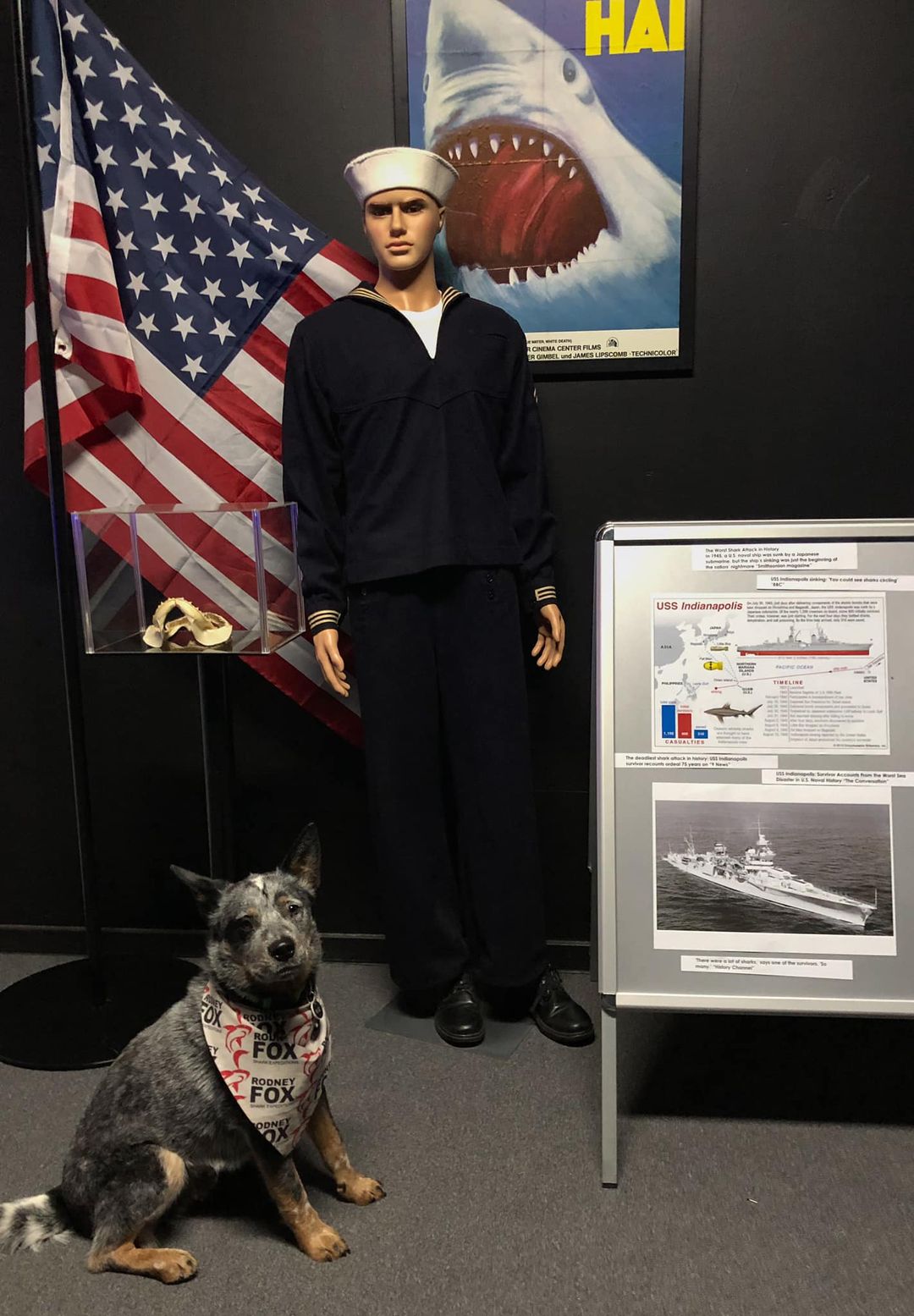

That brings us to the story of the USS Indianapolis,U.S. Navy heavy cruiser that was sunk by a Japanese submarine on July 30, 1945,

Rescue and aftermath

Of the nearly 1,200 men on board, as many as 900 survived the sinking. They were stranded in shark-infested waters(Oceanic Whitetips) with no supplies aside from life jackets and a few life rafts, however, and it took four days for help to arrive. Because of communications errors and other problems, the ship was not reported missing when it failed to arrive in Leyte Gulf as scheduled on July 31. The survivors were discovered by accident on August 2, when they were spotted by a passing U.S. naval aircraft. By that time only 316 of the men remained alive and were rescued. The U.S. government delayed reporting the tragedy until August 15, 1945, the same day it announced that Japan had agreed to surrender.

The story from seaman, Loel Dean Cox.

The first torpedo struck, without warning, just after midnight on 30 July 1945. A 19-year-old seaman, Loel Dean Cox, was on duty on the bridge. Now 87, he recalls the moment when the torpedo hit.

“Whoom. Up in the air I went. There was water, debris, fire, everything just coming up and we were 81ft (25m) from the water line. It was a tremendous explosion. Then, about the time I got to my knees, another one hit. Whoom.”

The second torpedo fired from the Japanese submarine almost tore the ship in half. As fires raged below, the huge ship began listing onto its side. The order came to abandon ship. As it rolled, LD, as Cox is known to his friends, clambered to the top side and tried to jump into the water. He hit the hull and bounced into the ocean.

“I turned and looked back. The ship was headed straight down. You could see the men jumping from the stern, and you could see the four propellers still turning.

“Twelve minutes. Can you imagine a ship 610ft long, that’s two football fields in length, sinking in 12 minutes? It just rolled over and went under.”

The Indianapolis did not have sonar to detect submarines. The captain, Charles McVay, had asked for an escort, but his request was turned down. The US Navy also failed to pass on information that Japanese submarines were still active in the area. The Indianapolis was all alone in the Pacific Ocean when it sank.

“I never saw a life raft. I finally heard some moans and groans and yelling and swam over and got with a group of 30 men and that’s where I stayed,” says Cox.

“We figured that if we could just hold out for a couple of days they’d pick us up.”

But no one was coming to the rescue. Although the Indianapolis had sent several SOS signals before it sank, somehow the messages were not taken seriously by the navy. Nor was much notice taken when the ship failed to arrive on time.

About 900 men, survivors of the initial torpedo attack, were left drifting in groups in the expanse of the Pacific Ocean.

And beneath the waves, another danger was lurking. Drawn by the carnage of the sinking, hundreds of sharks from miles around headed towards the survivors.

“We were sunk at midnight, I saw one the first morning after daylight. They were big. Some of them I swear were 15ft long,” remembers Cox.

“They were continually there, mostly feeding off the dead bodies. Thank goodness, there were lots of dead people floating in the area.”

But soon they came for the living, too.

“We were losing three or four each night and day,” says Cox. “You were constantly in fear because you’d see ’em all the time. Every few minutes you’d see their fins – a dozen to two dozen fins in the water.

“They would come up and bump you. I was bumped a few times – you never know when they are going to attack you.”

Some of the men would pound the water, kick and yell when the sharks attacked. Most decided that sticking together in a group was their best defence. But with each attack, the clouds of blood in the water, the screaming, the splashing, more sharks would come.

“In that clear water you could see the sharks circling. Then every now and then, like lightning, one would come straight up and take a sailor and take him straight down. One came up and took the sailor next to me. It was just somebody screaming, yelling or getting bit.”

The sharks, though, were not the main killer. Under the scorching sun, day after day, without any food or water for days, men were dying from exposure or dehydration. Their lifejackets waterlogged, many became exhausted and drowned.

“You could barely keep your face out of the water. The life preserver had blisters on my shoulders, blisters on top of blisters. It was so hot we would pray for dark, and when it got dark we would pray for daylight, because it would get so cold, our teeth would chatter.”

Struggling to stay alive, desperate for fresh water, terrorised by sharks, some survivors started to become delirious. Many started to hallucinate, imagining secret islands just over the horizon, or that they were in contact with friendly submarines coming to the rescue. Cox recalls a sailor believing that the Indianapolis had not sunk, but was floating within reach just beneath the surface.

“The drinking water was kept on the second deck of our ship,” he explains. “A buddy of mine was hallucinating and he decided he would go down to the second deck to get a drink of water. All of a sudden his life-preserver is floating, but he’s not there. And then he comes up saying how good and cool that water was, and we should get us a drink.”

He was drinking saltwater, of course. He died shortly afterwards. And as each day and each night passed, more men died.

Then, by chance, on the fourth day, a navy plane flying overhead spotted some men in the water. By then, there were fewer than 10 in Cox’s group.

Initially they thought they’d been missed by the planes flying over. Then, just before sunset, a large seaplane suddenly appeared, changed direction and flew over the group.

“The guy in the hatch of the plane stood there waving at us. Now that was when the tears came and your hair stood up and you knew you were saved, you knew you were found, at least. That was the happiest time of my life.”

Navy ships raced to the site and began looking for the groups of sailors dotted around the ocean. All the while, Cox simply waited, scared, in a state of shock, drifting in and out of consciousness.

“It got dark and a strong big light from heaven, out of a cloud, came down, and I thought it was angels coming. But it was the rescue ship shining its spotlight up into the sky to give all the sailors hope, and let them know that someone was looking for ’em.

“Sometime during the night, I remember strong arms were pulling me up into a little bitty boat. Just knowing I was saved was the best feeling you can have.”

Looking for a scapegoat, the US Navy placed responsibility for the disaster on Captain McVay, who was among the few who managed to survive. For years he received hate mail, and in 1968 he took his own life. The surviving crew, including Cox, campaigned for decades to have their captain exonerated – which he was, more than 50 years after the sinking.

Cox spent weeks in hospital after the rescue. His hair, fingernails and toenails came off. He was, he says, “pickled” by the sun and saltwater. He still has scars.

“I dream every night. It may not be in the water, but… I am frantically trying to find my buddies. That’s part of the legacy. I have anxiety everyday, especially at night, but I’m living with it, sleeping with it, and getting by.”

Blue pretty glad he wasn’t on the USS Indianapolis.

We have jaws from a Oceanic Whitetip on display and a uniform from one of the lucky survivors.